A systematic review is considered to be the highest level of evidence along with meta-analysis in our modern evidence based medicine. The concept of systematic review is simple, you search for all the available evidences in a particular topic, then you combine the evidence in a paper. Sounds simple enough, but it has very specific protocols and a few pitfalls. We'll discuss them shortly.

It'll be easier to understand the concept of systematic review, if you have a prior understanding of evidence based medicine. So if you are relatively new to the concept, I suggest you read my post about evidence based medicine first.

The Concept of Systematic Reviews

The first systematic review (and meta-analysis)history was performed by Karl Pearson is 1904. This review was about the efficacy of typhoid vaccine. The term systematic review was coined much later though, in 1995.

What is Systematic Review

As the name implies, it is a systematic and exhaustive search of literature in a specific topic and a review of the evidences gathered from all the studies found by the search process. The key properties of the systematic reviews are —

- The study must have a clear question, doing a systematic review is impossible if we don't know what we are trying to find out.

- The literature search must be systematic, so that it can be reproduced by any person.

- The literature search must be exhaustive, so that no evidence is left out.

- The literature search must be unbiased, hence multiple reviewers are necessary to mitigate subjective biases.

- Studies included for review should undergo quality checking to know the importance of each included studies.

- Systematic review is more than a simple literature review, the data must be analyzed and combined in a meaningful way.

Systematic Review and Meta-analysis

Both systematic review and meta-analysis are intertwined. A meta-analysis is a mathematical method of combining the results of multiple studies into an overall effect. Due to its very specific nature, meta-analysis cannot always be done especially when the available data is heterogeneous and not directly comparable.

A meta-analysis can be considered as a part of a systematic review. In most cases we need to do a systematic review in order to get the data we need for a meta-analysis.

The meta-analysis is a topic for another time though, this post is about systematic reviews.

Qualitative vs Quantitative Synthesis

Systematic review is not about regurgitating data from the included studies. The data must be analyzed and combined in a meaningful way so as to create a new piece of evidence. This process of generating new evidence is called synthesis.

There are two types of synthesis, qualitative and quantitative. The synthesis by a meta-analysis is called a quantitative synthesis, as it specifically quantifies the combined effect. Whereas the synthesis of data in the absence of a meta-analysis is known as the qualitative synthesis. As this post is about systematic review, we'll discuss the qualitative part of the data synthesis only.

Utility of Systematic Review

- Systematic review is the highest level of evidence along with the meta-analysis. Since it takes into account many studies, it has several advantages,

- Can form an overall effect even if the included studies differ from each other.

- Can eliminate bias in individual studies.

- The results are more generalizable than any of the included studies.

- When searching the literature for a particular issue, it's much easier to read one systematic review than, say, 10 individual studies. This is why systematic reviews are invaluable to clinicians.

- When citing literature, it's much easier to cite one systematic review than citing many individual studies. Systematic reviews, in most cases, qualify as original research so it's acceptable to cite the systematic review rather than each component studies.

Steps of a Systematic Review

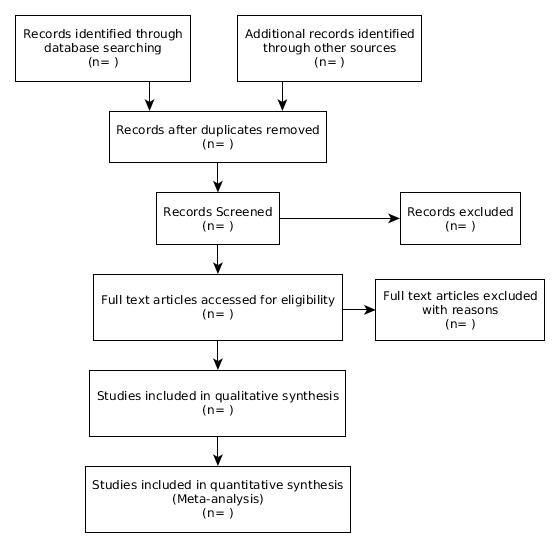

A systematic review follows a very specific protocol, so that it can be reproducible and objective. The most popular protocol is Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysisprisma or PRISMA for short.

(n = number of studies in each step)

Step 1: Find the Topic

Trust me, the first step is the most difficult step. It is not at all easy to find a suitable topic for a systematic review but it is somewhat easier than finding a topic suitable for a meta-analysis.

For a topic to be suitable, there have to be sufficient studies you can include. There is no hard numbers about this, you can even do a systematic review with just two studies. However, for a systematic review to be worthwhile, it needs more studies than just two. Since there is no standard guideline, I'll just give my personal opinion, I think four or more studies should be good if the topic is narrow.

It should also be taken into account whether there are other systematic reviews on the same topic. Having multiple systematic reviews on the same topic is not only redundant, but it also creates unnecessary confusion among the readers. However if the existing systematic reviews are outdated with significant developments since it was published and the authors have no intention to update it, a new systematic review may be considered appropriate.

It is best to choose a topic in your field of expertise because you will be able to appreciate the importance of the topic and the included studies better than others. Your critical appraisal of the included study will also be more appropriate. It is also often recommended to work with someone who is familiar with systematic reviews, however, not everyone can have that privilege.

Step 2: Find the Team

This is just as important as any step. It goes without saying that you need people you can work with, especially so in case of a systematic review because close association is needed between the authors to perform a systematic review in the proper way.

First thing to try is to get someone who is familiar with the process of systematic review, it will make the process a lot easier. If you can't then it's gonna be blood, sweat and tears for you, trust me, I had to go through that before I learned it. Anyway, you need to have someone senior, preferably a veteran clinician in your team, who can assess your work and suggest necessary corrections. If you are starting out in the academia you probably don't yet have the expertise to judge the value of a work as good as an experienced person can.

You also need team members at your own level who will share the workload. As we will discuss later, many processes have to be repeated by multiple team members independently, so equal participation is very important. Also solving disagreements by discussion and possibly argument is an integral part of any systematic review. So in my opinion the main authors should be of same ranks so that seniority doesn't influence the arguments, as it may give rise to bias in the study.

A team for a systematic review must contain at least three members, two authors are essential for the literature search and study quality assessment and the third author acts as a supervisor. There can be any number of members in the team, however, every member should have clearly defined tasks in order for the study to be properly executed. The literature review and quality assessment can also be done by more than two authors, in fact, the more the merrier. However it will get increasingly difficult to co-ordinate as the number of reviewers increase.

It's recommended that the members come from a specialty related to the study topic. If a topic spans multiple specialties, members from each of those specialties would be useful in improving the quality of the study. However this is optional and not mandatory by any means.

Step 3: Form the Question

This is the heart of the systematic review. The whole systematic review centers around the research question.

The research question determines how many studies will qualify for inclusion. Make the question too narrow, and there won't be enough studies to include. Make the question too broad and there will so many studies that you can't reasonably handle them all. You have to find the perfect balance between these two.

This is why a question like "how to manage HIV in adults" may be too broad whereas "what is the efficacy of potassium iodide in entomopthoromycosis" may be a little too narrow. However, there are exceptions though. The Cochrane Library contains hundreds of systematic reviews on relatively broad topics. On the other hand if there are sufficient researches in a particularly narrow topic, a systematic review may become feasible.

The PICO method: The PICO is one of the standard methods to help formulating a research question. PICO stands for Patient, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome. An example of a PICO question would be "does pigtail catheter drainage have better clinical outcome than percutaneous needle aspiration in patients with liver abscess".

Step 4: Set the Criteria

Before you can start looking for studies to include, you must clearly define your criteria for inclusion and exclusion. This will depend on your study question entirely. However some types of studies are almost always excluded from systematic reviews including opinion and viewpoint articles, letters, editorials, expert opinions, case reports, case series etc. Other review articles are also excluded.

Every study you find by literature search must be evaluated by these criteria. You need to justify why you would include or exclude a study. One thing to keep in mind though, be inclusive, if you can't decide whether a study should be included or not, just include it and think later. When in doubt, include.

Step 5: Search Literature

This is the most laborious part. You have to search electronic databases and other sources for studies related your question. Let's see what the different sources are —

- Electronic Databases

- This is the most common and relatively easy source to search. You just fire up a web browser, go to the respective search engines and use your keywords to search through their indexed literature. There are many electronic databases and we will discuss them separately in a short while.

- Snowballing

- The studies you consider for inclusion may have other relevant studies in their reference lists. You might use these to look for further studies.

- Hand Searching

- This is the age old technique of searching printed journals by hand. You may go to your institution's library and rush through the pages. Frankly, I have never done this.

Among this the electronic database searching is considered to be the most important and we need to take a closer look at the most common search engines used for this purpose.

- PubMed

- In my humble opinion this is the best literature search engine there is. You can probably find almost all of the relevant studies here. It's free and it supports advanced search strategies. We will see them when we discuss about forming the search term.

- EMBASE

- Many people swear by it but it's not free. It's damn costly so if you can afford buying access to EMBASE, you also owe me a rather nice treat for this post. For rather poor folks like me the only hope of accessing it is through institutional libraries. And if your institution doesn't have access too, then you just have no other option but to ignore it entirely, which I have always done.

- Cochrane Library

- Very nice place, very nice content. They serve you clinical trials on a platter. Not much good for other types of studies though.

- Google Scholar

- Too many search results, literally in the range of tens of thousands. To make it manageable you have narrow the search term down to the point where it no longer makes sense.

- CNKI

- This is the Chinese index of literature. Naturally majority of the studies are in Chinese. You need to know some language-foo to use this thing. Or you could just use Google Translate.

Search term Forming the appropriate search term requires some amount of skill. Suppose you want to search for role of sanitizers in COVID-19. Just searching "sanitizer COVID-19" will probably not give all the results you want. Because sanitizers may be mentioned as hand-sanitizer, hand-rub, hand hygiene etc. COVID-19 on the other hand may be written as COVID19, SARS-COV-2 etc. You have two options to catch all of them.

- Use multiple search terms

- "sanitizer COVID-19", "hand hygiene SARS-COV-2", "hand-rub COVID19" so on and so forth.

- You can use advanced search features

- (sanitizer OR hand-sanitizer OR hand-rub OR hygiene) AND (COVID-19 OR COVID19 OR SARS-COV-2)

These examples are given from the top of my head, they have neither been tested nor used in actual search, so take them as such.

I personally prefer the later style. It's concise, efficient and easily reproducible. Here is the advanced search page in PubMed

Step 6: Rinse and Repeat

You'll need to loop through Step 3 to 5 several times in order to find the optimal scope of your study. Unless you perform the literature search you won't know whether the scope have been too broad or too narrow. Based on this the study question may need a little tweaking in order to find the sweet spot. Once you are satisfied with the study scope, you can proceed to the next step.

Step 7: Include Studies

This is where the real fun begins, and by fun I mean reading through hundreds of lines of text and arguing with each other which studies should make the cut.

All the search results you found in step 5 need to be collected together. Then all the duplicate studies will have to be removed. You could do it by hand theoretically, but I highly recommend you use a citation manager for this. I personally have been using Zotero but I'm not endorsing it, you can use whichever suits your needs.

Now at least two authors must independently screen each study title to decide whether it should be considered or not. There will be lots of junks, so expect to discard a large portion of the results in this step.

In the next step the studies which made it through the previous stage will be evaluated by their abstracts, again by two authors independently. Remember that any study that makes it through this stage cannot be discarded further down the line without mentioning explicit reason for doing so.

The next stage is to access the full text of the articles. Again, three options, buy'em, borrow'em or steal'em. I already mentioned some questionable stuffs in the noob section of the evidence based medicine post, so I'm not gonna do it here too.

Anyway now you have to evaluate each paper by the full text, by two authors independently. If a paper finally makes it to the study, fine. If one does not, you have to mention the reason explicitly in your paper.

Now the most important part. If in any stages above there is a disagreement between the two authors, which will always happen, it should be settled between the two by discussion. The authors may also challenge each other to a duel if they so desire. However in case the negotiations fail, the third author, usually the supervising author, should break the tie.

I've mentioned "two authors" in every step because that's common, however you may involve three authors for independent evaluation. In fact you may include as many as you want. Theoretically the more the reviewers, less the chance of bias. However, practical warning, make sure it doesn't turn into a Mexican standoff.

Step 8: Evaluate Risk of Bias

A chain is only as strong as its weakest link and a systematic review is only as good as its component studies. If the included studies are full of bias then the systematic review will be of little use. As a reviewer it's your job to evaluate each study for its risk of bias. The recommended tool for randomized controlled trails is the Risk of Bias toolrob by Cochrane Collaboration. The risk of bias assessment for other types of studies have been mentioned in the evidence based medicine post.

Step 9: Extract Data

Now you have to get the data out of the included studies for further analysis. We are mostly interested in the results section of the papers and the methods section to some extent. Extract all the data you think you might need for the analysis.

Make tables whenever you can. Tables should be concise and data should be as compact as possible. Don't make tables that span many pages. Tabulate only what you need to reach a meaningful conclusion.

I also suggest to make short summaries of each study at this stage in a separate draft. Focus on the methods and the results section. These summaries should be no more than 4 to 5 sentences long. I personally feel like making these summaries help me in the next stage, but this is completely subjective and you should do whatever works for you.

Step 10: Do the Synthesis

As we have discussed earlier, this post will limit itself to the qualitative synthesis of the data. The quantitative synthesis in the meta-analysis is a topic for another post.

If you have tabulated the data in the previous step, try to make a short summary of it. Do not repeat the data, just write your impression of it. Does the table give any insight into the topic? Great, put it down. Tables are just dry data, your readers expect to find its meaning in the text.

Next you need to combine the data from the studies that didn't fit into the table. The summaries you may have made into the last step may come into play here. Observe carefully, do you find any special similarities or dissimilarities? Write it down.

Next whatever you think is important in the included studies but didn't fit anywhere maybe summarized in short. But do make it brief.

In the end, try to form an overall picture of the grand scheme and put it down briefly.

Step 11: Write the Manuscript

Finally the moment we all wait for is here. The study is done and now its time to write the manuscript. There is not much to say here. Usually a systematic review is written under the following headings —

- Introduction

- Methods

- Literature Search

- Study Selection

- Data Extraction

- Risk of Bias Assessment

- Data Synthesis

- Results

- Included Studies

- (Synthesized Data)

- Discussion

- Conclusion

Now different journals will have different formatting requirements, but this is a generic structure of writing a systematic review. And one thing, you need to include a PRISMA diagram in your manuscript, you may adapt the template provided in this post for that purpose.

Step 12: Revise, Revise and Revise

Revising the manuscript has no alternative. You'll find tons of mistakes that you had inadvertently made. You may even find new insights while reviewing the manuscript. This is why a manuscript may change drastically in the course of reviewing. Ask each author to review the manuscript at least once.

Done? Congratulations! You have just finished a systematic review.

Publish

Now that you have finished writing the systematic review, you have to send it out there so that others may benefit from it.

Almost all journals accept systematic reviews, so that's a good thing. The bad thing is that many of them expect a systematic review to be written by an established expert which makes life a bit difficult for young researchers. However, if you look hard enough you'll find a journal for you.

In recent years preprint servers have become quite popular. A journal takes months to process your paper, whereas a preprint server gets it out there in a matter of days. However they are not a replacement for journal publication. So you may decide to send it to both a preprint server and a journal, but be sure to read all rules and regulations, especially because posting the paper on a preprint server may disqualify it from a small number of journals.

Caveats

Doing a systematic review is often associated with some difficulties. A few of them are listed here.

- Finding the topic

- To do a systematic review on a topic there must be sufficient numbers of primary studies like randomized controlled trials. However, if a systematic review already exists on the same topic then there's no point in doing the same. So this is the catch 22, for a topic to have multiple good quality studies it must receive good attention in the academia, but if a topic receives enough attention then someone would have already performed a systematic review on it. This is why it is very difficult to find an unoccupied ground.

- EMBASE

- Some people swears by EMBASE database search, however as I mentioned earlier its beyond the reach of many. Many studies just ignore the database altogether, as do I.

- Synthesis of Heterogeneous Data

- If the data from the included studies is too much different from each other then it may be very difficult to combine them together. In such cases just summarizing the data from each study and attempting to form an overview may be a necessary approach.

This is by no means an exhaustive list of difficulties faced during a systematic review. I'd be very interested to hear your story regarding systematic review and what difficulties you faced.

Example

I'm going to use one of my own systematic review as an example, not out of vanity but because I want to show you how I followed the above steps and what the end result looked like.

The study is in the preprint titled Utility of Cloth Masks in Preventing Respiratory Infections: A Systematic Reviewmyprecious.

I'm by no means an expert in systematic review and I'm still learning actively. If you find any mistake in the article, please point out in the comment section. I'm very interested in hearing your opinion or experiences regarding systematic reviews as well.

- Jessica Gurevitch, Julia Koricheva, Shinichi Nakagawa et al. Meta-analysis and the science of research synthesis. Nature. 555 (7695): 175–182. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature25753

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group (2009) Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med 6(7): e1000097. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

- Higgins JP1, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, Jüni P, Moher D, Oxman AD, Savovic J, Schulz KF, Weeks L, Sterne JA; Cochrane Bias Methods Group; Cochrane Statistical Methods Group. The Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011 Oct 18;343:d5928. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.d5928.

- Agnibho Mondal, Arnavjyoti Das, Rama Prosad Goswami. Utility of Cloth Masks in Preventing Respiratory Infections: A Systematic Review. medRxiv 2020.05.07.20093864; doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.05.07.20093864

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

Write a comment: